Bangladesh's Far-Right Problem: When Voting Means Voting Against God

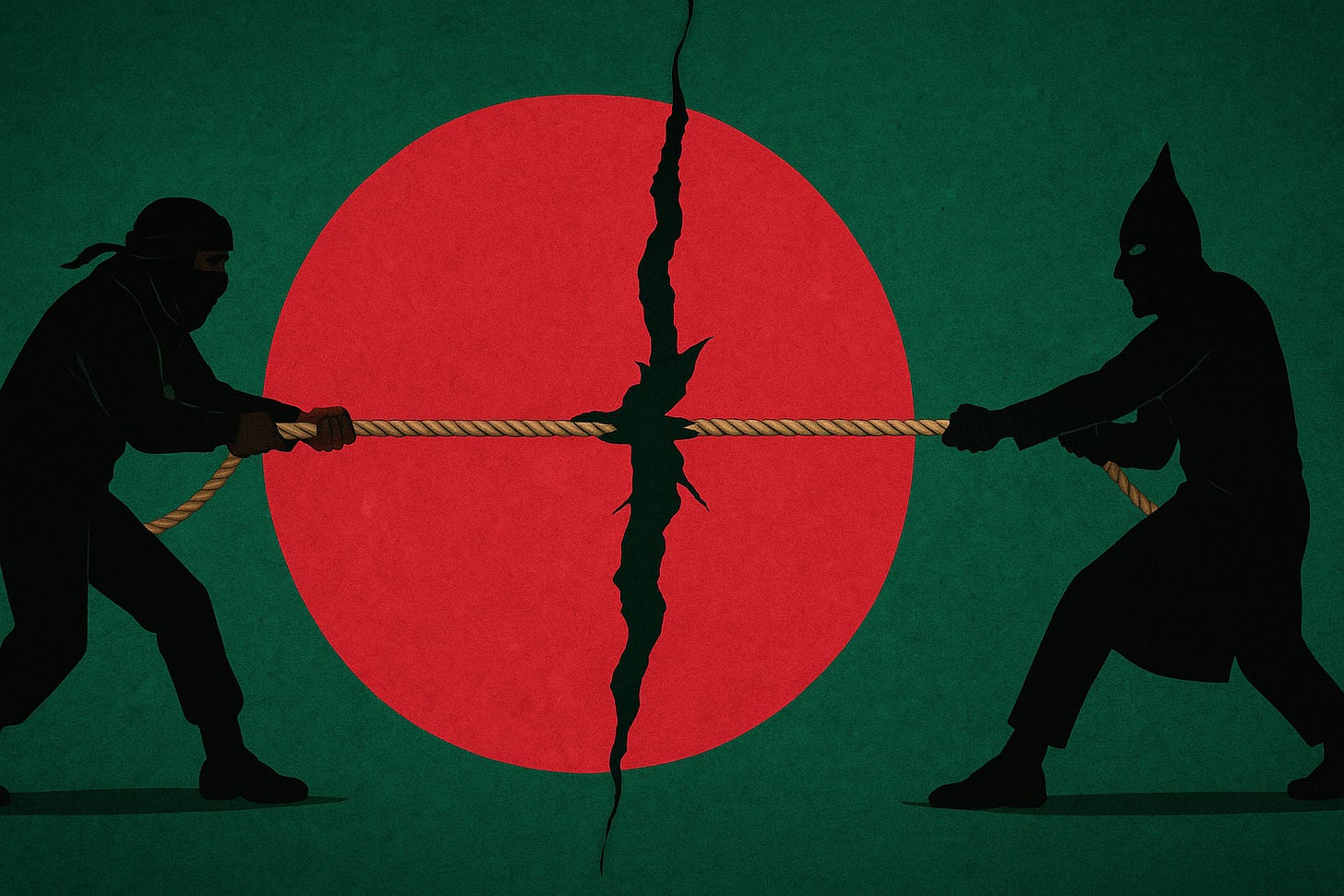

SecDev's latest research shows that in Bangladesh, the ballot box has become a battleground for the soul.

History rarely announces when it is shifting gears. But Bangladesh’s upcoming 2026 election carries the unmistakable weight of a turning point, one where the outcome will determine not merely which party governs, but whether democratic governance itself survives. The religious far-right, largely comprising actors sympathetic to or dir…